.

.

.

Roman Bystrianyk

Health Sentinel

Monday, 14 December 2009 02:04

Many of us have a picture of the 1800s that has been colored by a myriad of filters that have led us to a nostalgic and romantic view of that era. We picture a time where gentleman callers came to call upon a well-dressed lady in a finely furnished parlor. We imagine a time where people leisurely drifted down a river on a paddle wheel riverboat while sipping mint juleps and a time of more elegant travel aboard a steam train traveling through the countryside. We picture an elegant woman dressed in a long flowing gown leaving a sleek horse drawn carriage with the aid of a well-dressed man in a top hat. We think of those times where life was simple, ordered, in a near utopian world free of the many woes that plague modern society.

But if we remove those filters and cast a more objective light upon that time a different view emerges. Now imagine a world where workplaces had no health, safety, or minimum wage laws. It was a time where people put in 12 to 16 hours a day at the most tedious menial labor. Imagine bands of children roaming the streets out of control because their parents are laboring long days. Picture the city of New York surrounded not by suburbs, but by rings of smoldering garbage dumps and shantytowns. Imagine cities where hogs, horses, and dogs and their refuse were commonplace in the streets. Many infectious diseases were rampant throughout the world and in particular in the larger cities. This is not a description of the Third World, but was a large portion of America and other western cities only a century or so ago.

Our perceptions of history encompass a lot of willful rejection of knowledge. It is easier and more convenient to wax nostalgically rather than acknowledge an uncomfortable reality. We insist on creating a more pleasant historical illusion, but by doing so we cloud a historical issue in a way that promotes a bad misunderstanding of the past, and has every potential to result in bad misunderstandings of the future.

- 1807-1812: Glasgow, England – Measles accounts for 11% of all deaths.

- 1830s: United States – Eastern seaboard cities have a mortality rate from tuberculosis of 400 per 100,000.

- 1845-1850: Ireland – Great Famine claims approximately 2 million lives, some from starvation, but far more from typhus and other epidemics consequent upon malnutrition and social collapse.

- 1854: New York City – Nearly 2,500 people are killed by cholera.

- 1847-1861: 2,589,843 Russians contract Cholera and over 1,000,000 die.

- 1861-1865: American Civil War – The Union Army loses 186,216 men to disease, twice the number killed in action; nearly half were claimed by typhoid and dysentery.

- 1855: Yellow fever rages in Norfolk and Portsmouth Virginia, Louisiana, and Mississippi. In the Virginia plague area one out of five die of the fever, its victims buried wholesale in trenches without coffins.

- 1865: New York City – Fifteen thousand tenement houses have been built, many of which are hardly more than “fever nests”.

- 1867-1872: Hospice des Enfants Assistés reports 1,256 cases of measles and 612 deaths with a mortality of 49%. Malnutrition was known to be rife in orphanages at the time.

- 1871: A terrible smallpox epidemic which threw both New York and Philadelphia into morning. It killed over eight hundred people in the former city, more than ever before in its history, while the latter the deaths nearly reached two thousand.

- 1871-1872: England – Smallpox epidemic 42,200 deaths suggesting 200,000 or more cases.

- Europe – One of the worst epidemics in European smallpox history.

- Prussia – Great smallpox epidemic. Despite strict vaccination laws 69,839 die from smallpox more than in any other northern state.

- Chicago – Despite a high vaccination rate, over two thousand people contract smallpox and more than a fourth of these die. The fatality among children under five is the highest ever recorded.

- 1873: Memphis – Suffers attacks of yellow fever, smallpox, and cholera simultaneously. People flee the city leaving half of the houses vacant.

- 1874: Bloomington, Illinois – All kinds of garbage and human and animal waste had been thrown into small streams running into Sugar Creek and became known as the “North and South Sloughs”. Over the years the Sloughs “became a … sodden pool of stench that was the breeding places for disease … because it drained sewage into the community’s primary water source, Sugar Creek.”

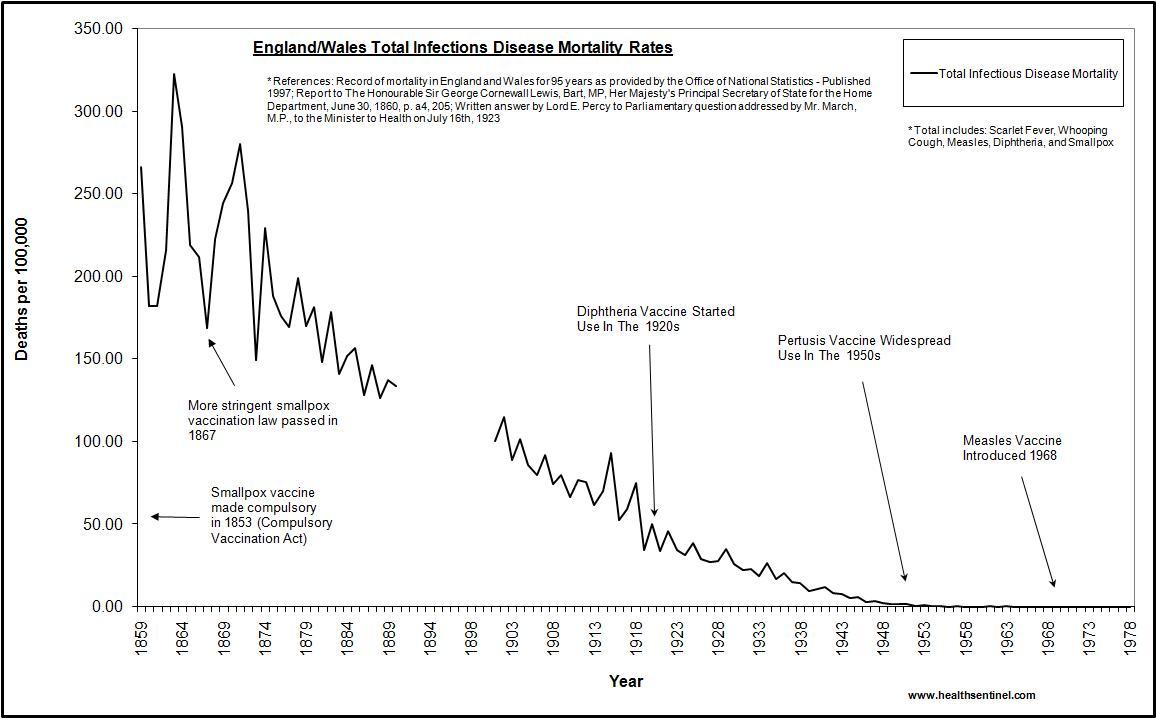

These historic points show that infectious diseases were a constant and deadly threat during these times. England was the country that early in 1838 began to keep statistics on causes of death and is the best source to find out the devastating impact of these infectious diseases. Using this raw data a number of graphs were generated to understand these plagues.

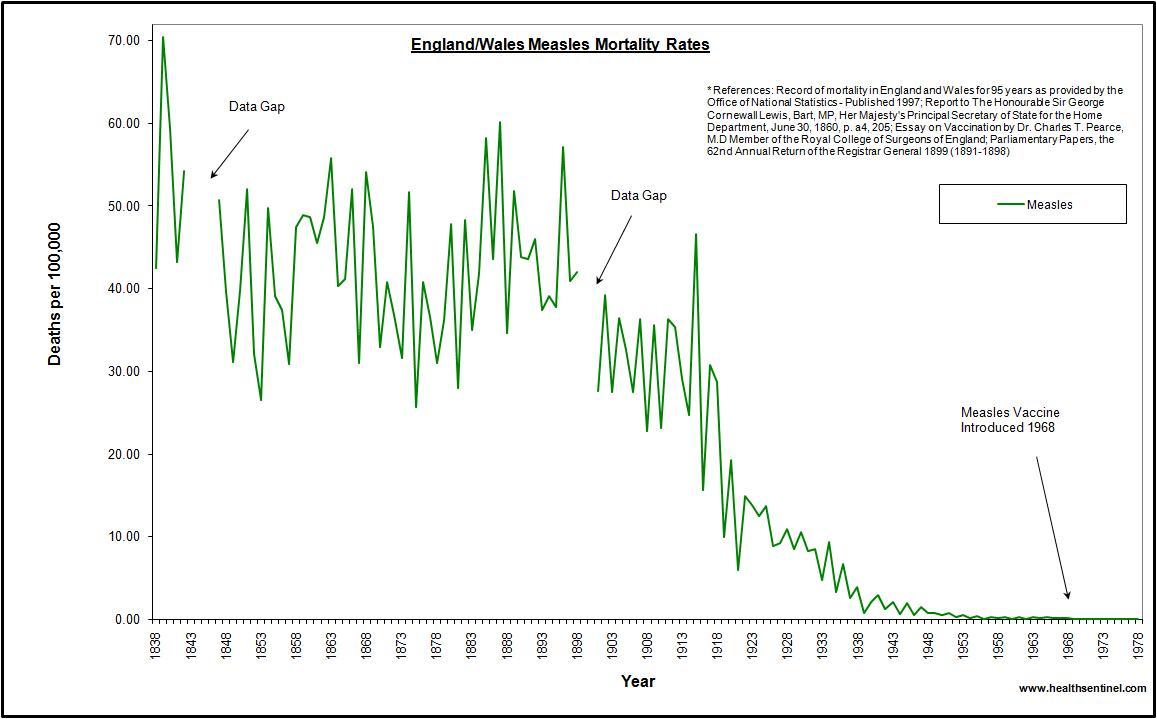

Measles was one of the very potent infectious killers. As the graph clearly shows deaths were rampant throughout the 1800s and then began a rapid decline and virtually became a relatively benign disease by the mid 1900s causing very few deaths. By the time the measles vaccine was introduced approximately in 1968 the death rate for measles had fallen by over 99%.

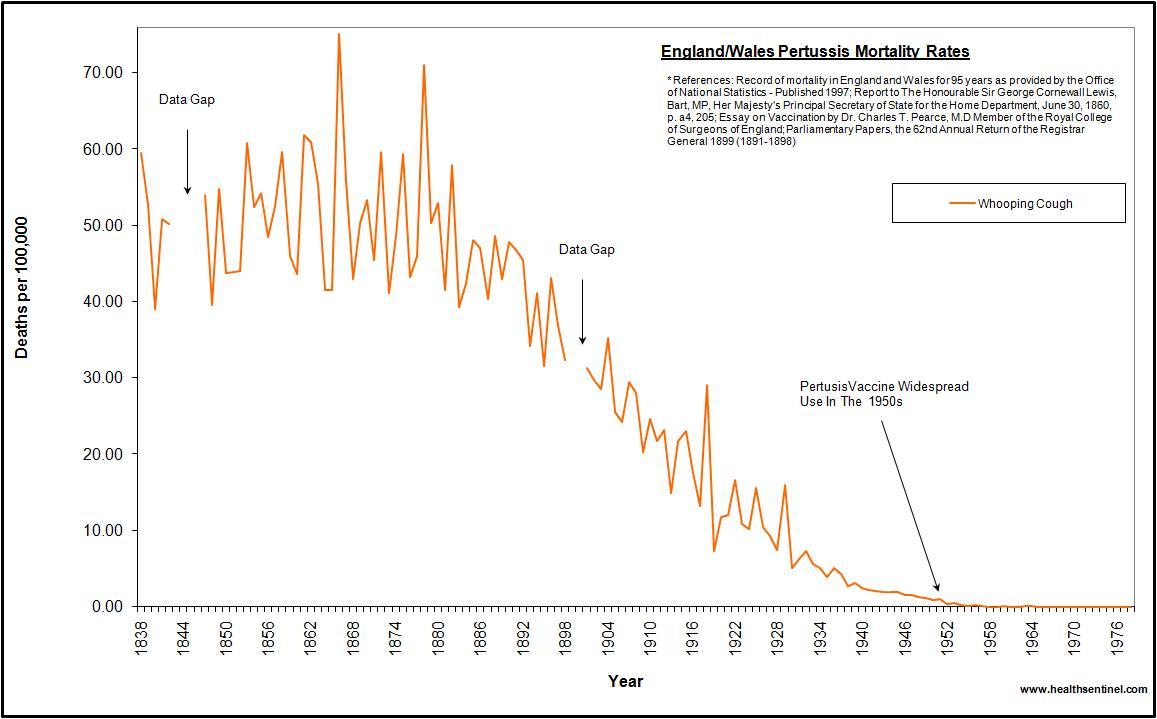

Whooping cough, also known as pertussis, was an infectious killer on par with measles killing many people throughout the 1800s. Similar to measles a slow and steady decline began in the late 1800s becoming much less of a deadly threat by the mid 1900s. By the time the whooping cough vaccine was introduced the 1950s the death rate had also fallen by over 99%.

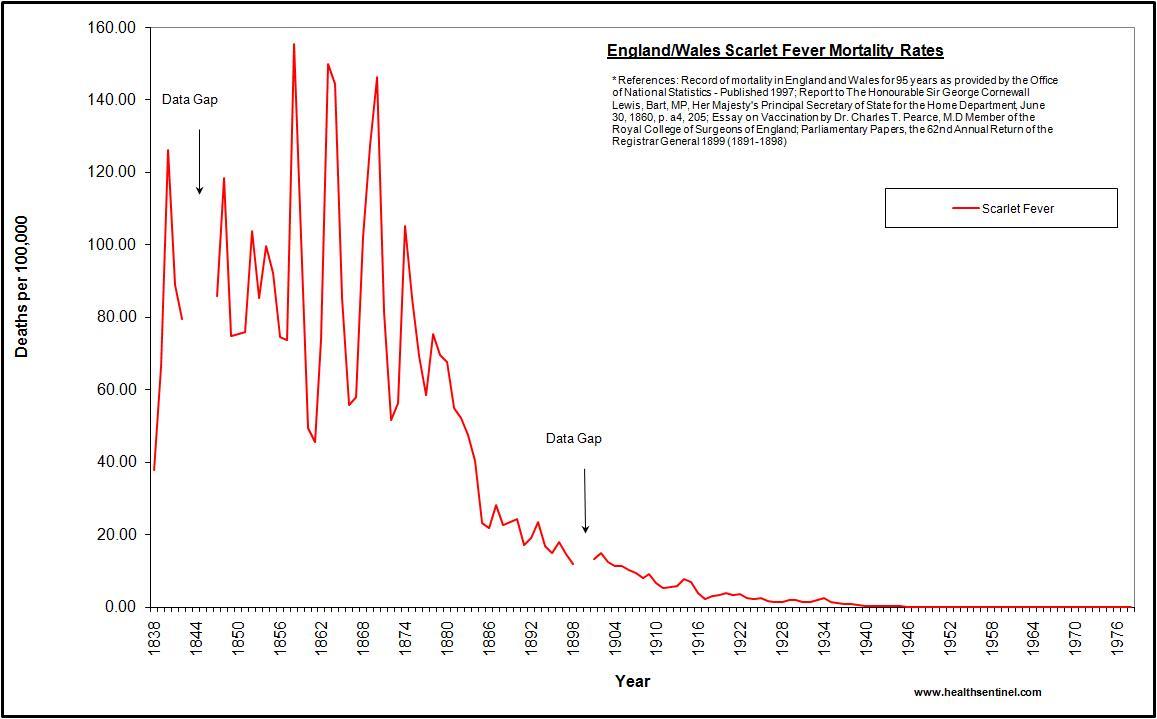

Scarlet fever was twice the killer that measles and whooping cough were during the 1800s. Similar to measles and whooping cough, scarlet fever also made a rapid fall in death rate starting in the late 1800s and becoming virtually benign by the mid 1900s. Although a scarlet fever vaccine was patented in 1924 it was never in widespread use.

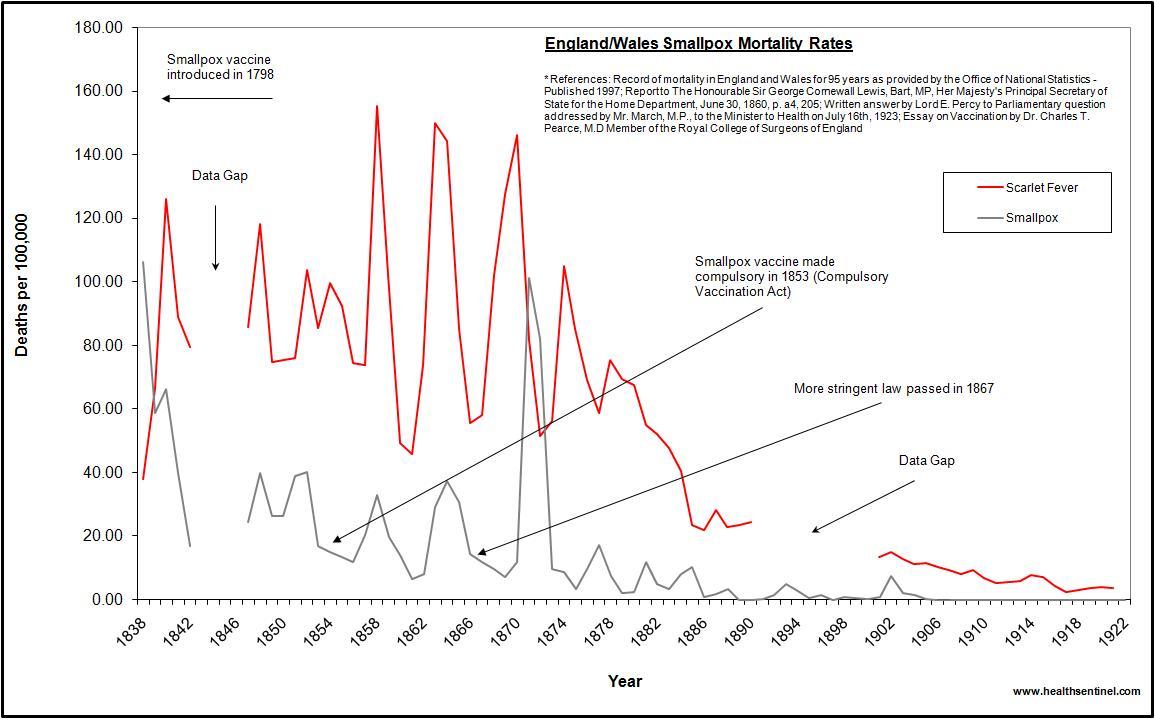

A lesser but still major killer than measles, whooping cough, or scarlet fever was smallpox. Smallpox like scarlet fever became exceptionally deadly periodically interestingly in somewhat synchronized with scarlet fever. In the late 1700s a man by the name of Edward Jenner created a vaccine he believed would protect against smallpox. Jenner believed that if he could inject someone with cowpox, the germs from the cowpox would make the body able to defend itself against the dangerous smallpox. However for the next 80 years despite strong vaccination laws in England smallpox continued to take many lives culminating with a massive smallpox pandemic in 1872. Again, similar to the other infectious diseases already discussed the death rate from smallpox finally began to decline by the late 1800s and became less of a killer by the early 1900s.

This historic research shown in the form of these graphs clearly demonstrates that vaccines were not the key factors in the reduction in deaths from these deadly diseases. Both whooping cough and measles death rates had fallen by 99% before the introduction of vaccines. A much bigger killer, scarlet fever, had its death rate also declined into virtual obscurity without the use of any vaccine. Smallpox remained a significant killer despite having a vaccine in use for approximately 80 years and then that disease’s death rate declined along at the same time as the other infectious diseases.

Sources:

Record of mortality in England and Wales for 95 years as provided by the Office of National Statistics – Published 1997

Report to The Honourable Sir George Cornewall Lewis, Bart, MP, Her Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State for the Home Department, June 30, 1860, p. a4, 205

Essay on Vaccination by Dr. Charles T. Pearce, M.D Member of the Royal College of Surgeons of England

Parliamentary Papers, the 62nd Annual Return of the Registrar General 1899 (1891-1898)

Arthur Charles Cole, A History of American Life Volume VII – The Irrepressible Conflict 1850-1865, The Macmillan Company, 1934, pp. 179-204

Allan Nevins, A History of American Life Volume VIII – The Emergence of Modern America 1865-1878, The Macmillan Company, 1927, pp.318-331

Bloom Arnold, FRCP, “Section of Medicine, Experimental Medicine & Therapeutics – Measles”, Proc. Roy Soc. Med. November 1974, Vol. 67, pp. 1109-1136

Clive E. West, Ph.D., D.Sc, “Vitamin A and Measles”, Nutrition Reviews, February 2000, Vol. 58, No. 2, S46-S54

Porter, Roy, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, Harper Collins Publishers, 1997, pp. 397-427

Baxby, Derrick, “The End of Smallpox”, History Today, March 1999, pp. 14-16

Encyclopedia Britannica, The Saalfield Publishing Company, Akron, Ohio, 1903, pp. 6119-6121

Rice, Thurman, A.M., MD, The Conquest of Disease, The Macmillan Company, 1932, pp. 68, 121-122

Thomas Neville Bonner, Medicine in Chicago 1850-1950 A Chapter in the Social and Scientific Development of a City, The American History Research Center, Madison, Wisconsin, 1957, pp. 175-199

Lucinda McCray, A matter of life and death: health, illness and medicine in McLean County, 1830-1995, Bloomington Offset Process, Inc., 1996, pp. 45-61